ABOUT ERICH WARSITZ

______________________________________

THE FIRST JET PILOT

On 18 October 1906 Erich Warsitz, son of senior engineer Robert, was born at Hattingen in the Ruhr. In his youth began, together with his practical tuition and technical studies, his aeronautical training as a sport flier with the academic group of fliers at Bonn/Hangelar, where he got his A-2 licence. In stages subsequently came the B-1 and B-2 training at various aerodromes of the contemporary sports associations, and further training at DVS (German Commercial Pilot School) at Stettin for the C-2 (land aircraft and commercial carriage of persons) and all licences for flights over the sea. Meanwhile he was awarded the major K-2 aerobatics licence, passed the blind-flying training and obtained the navigation certificate for short distances.

He then took employment as a sporting aircraft instructor and was later transferred to the Reichsbahnstrecke (i.e. the Railway section, a cover name for long-distance flying experience, a unit concealed within the 100,000-man Weimar standing army) as flight instructor, senior flight instructor and then training leader. In 1934 orders arrived drafting him to Rechlin, the Luftwaffe’s test centre. At that time the German aviation industry was operating at full blast, and at Rechlin Erich Warsitz was soon flying everything the aircraft factories could produce.

He then took employment as a sporting aircraft instructor and was later transferred to the Reichsbahnstrecke (i.e. the Railway section, a cover name for long-distance flying experience, a unit concealed within the 100,000-man Weimar standing army) as flight instructor, senior flight instructor and then training leader. In 1934 orders arrived drafting him to Rechlin, the Luftwaffe’s test centre. At that time the German aviation industry was operating at full blast, and at Rechlin Erich Warsitz was soon flying everything the aircraft factories could produce. A few years before, in 1931, the Army Weapons Office testing ground at Kummersdorf had taken over research into liquid-fuel rockets. In 1932, Wernher von Braun, after the Second World War the father of rocket technology/space science in the United States and chief architect of the Saturn V vehicle that propelled the Apollo spacecraft to the Moon, designed a rocket which used high percentage spirit and liquid oxygen. With this he made the first experiments. In 1934 he fired his second rocket type, the A2, from the North Sea island of Borkum.

Having completed the programme of experiments, it now interested von Braun to discover how an aircraft would behave if fitted with the rocket motor as its propulsion system. For this he needed an aircraft and support team, in those days no easy search! Officially the highest levels at the Army High Command (OKH) and the Reich Air Ministry (RLM) were opposed to such "fantasies", as they called them. Many people, technicians and academic experts in positions of influence in aeronautics, maintained that an aircraft driven by a tail thrust would experience a change in the centre of gravity and flip over. Very few believed the contrary, but one of them was Dr Ernst Heinkel, one of the great aeronautical designers of the age.

Following his offer of unhesitating support, Heinkel placed at the disposal of von Braun an He 112 fuselage shell less wings for the standing tests. Von Braun had advanced far enough to begin trials. A great tongue of flame from the rocket motor roared through the fuselage tail to set up the back thrust.

Following his offer of unhesitating support, Heinkel placed at the disposal of von Braun an He 112 fuselage shell less wings for the standing tests. Von Braun had advanced far enough to begin trials. A great tongue of flame from the rocket motor roared through the fuselage tail to set up the back thrust.At this time, late in 1936, Erich Warsitz was seconded by the RLM to Wernher von Braun and Ernst Heinkel, because he had been recognized as one of the most experienced test-pilots of the time and also had an extraordinary fund of technical knowledge, and last but not least because he was not married. This sounded to Erich Warsitz like a suicide mission!

Read MORE >>

.

HEINKEL HE 112

___________________________

In 1937, working closely with von Braun, Erich Warsitz undertook the initial ground and flight testing of the Heinkel He 112 fitted with von Braun’s rocket engine. In parallel he tested another He 112 fitted with the Walter-rocket.

Hellmuth Walter had also been commissioned by the Reich Air Ministry to build a rocket engine for the He 112. In principle both engine worked much the same way but Walter used a different rocket fuel to von Braun: whereas the latter’s engines were powered by alcohol and liquid oxygen, Walter engines had hydrogen peroxide and calcium permanganate as a catalyst. Von Braun’s engine used direct combustion and created fire, the Walter devices hot vapors from a chemical reaction, but both created thrust and provided high speed.

Erich Warsitz: "After months of untiring effort we started to look for somewhere to carry out the flight experiments under conditions of secrecy and reasonable safety."

Erich Warsitz: "After months of untiring effort we started to look for somewhere to carry out the flight experiments under conditions of secrecy and reasonable safety."The RLM agreed to lend a large field about 70 kilometers east of Berlin, listed as a reserve airfield in the event of war. This was Neuhardenberg, which had no buildings or facilities. A number of marquees were erected to house the aircraft.

Flying the He 112 with von Braun's rocket technology Erich Warsitz made the first flight from the airfield at Neuhardenberg in 1937, but these tests did not all go well.

Erich Warsitz: ”The plan was to take off under normal engine power, climb to altitude, increase speed, level off, ignite the rocket. Seconds after engaging the rocket motor, quantities of smoke and gas began to enter the cockpit. From the corner of my eye I saw flames behind me in the fuselage. My speed was increasing. I shut down the Junkers Jumo engine to keep my speed level. Now I was flying under rocket power alone. A very high temperature accompanied the gases coming into the cockpit. I told myself: “Lose height and get her down somewhere!” I lost more altitude by side-slipping without increasing speed. Almost at ground level I crossed the airfield boundary, but had no time to get the wheels down. Suddenly the 30 seconds was up, the rocket cut out and I landed wheels-up on the airfield at the same instant. I jumped clear and ran! Scarcely had I done so than the aircraft was afire.”

The first He 112 flight using the auxiliary rocket motor fell short of hopes and expectations, but was successful insofar as it proved to official circles that an aircraft could be flown satisfactorily using the rear-thrust principle and would not flip over as many influential gentlemen of the time asserted.

The first He 112 flight using the auxiliary rocket motor fell short of hopes and expectations, but was successful insofar as it proved to official circles that an aircraft could be flown satisfactorily using the rear-thrust principle and would not flip over as many influential gentlemen of the time asserted. The subsequent flights with the He 112 at Neuhardenberg used the Walter rocket instead of von Braun's. It had been designed originally for its simplicity and safety. The disadvantage lay in the relatively high specific consumption, though this was not critical for test flights. It was more reliable, simpler to operate and the dangers to pilot and machine were less.

HEINKEL HE 111

___________________________

The Reich Air Ministry (RLM) had suddenly developed an interest in rocket boosters, which fitted below the wings of heavily loaded bombers, to assist take-off from small aerodromes and auxiliary fields with short runways. Once in the air the containers would be discarded by parachute for re-use. This development was worked on by the Hellmuth Walter. There now began a very close cooperation with the Walter factory. The first standing trials of their boosters were held at Neuhardenberg using an He 111E placed at our disposal by Heinkel.

Erich Warsitz: "By the early summer of 1937 the Walter take-off boosters were so far advanced that I could test fly an He 111 with them. The weather was highly unfavorable with cloud cover at 1000 meters. Normally such maiden flights, in which there is a possibility that the aircraft might blow up and the aircrew rely on their parachutes deploying, are made at several thousand meters. ‘Speed and altitude are half your salvation’ is an old flying motto!

Erich Warsitz: "By the early summer of 1937 the Walter take-off boosters were so far advanced that I could test fly an He 111 with them. The weather was highly unfavorable with cloud cover at 1000 meters. Normally such maiden flights, in which there is a possibility that the aircraft might blow up and the aircrew rely on their parachutes deploying, are made at several thousand meters. ‘Speed and altitude are half your salvation’ is an old flying motto! The aircraft held its course straight and true and climbed phenomenally with the added thrust of two 300-kg rockets. The angle at which they were fitted made the aircraft tail-heavy however. The airspeed wanted, so far as I remember, was 250 kms/hr, but that was not a decisive factor. The booster rockets had their 30-second burn and we made a smooth landing.”

The RLM was very enthusiastic about this development, particularly because the initial test programme had been relatively trouble-free, and had given aircraft manufacturers the following specification: A standard aircraft – such as the He 111 – had to reach 20 meters altitude with a take-off run of 600 meters. Within a short time, by building into the fuselage of the He 111 additional water tanks and then filling the space with eight cement bombs and sandbags, Erich Warsitz (on the extreme right of the main picture above) began to set records for heavyweight take-offs.

Von Braun also worked on the development of rocket boosters, but major difficulties put him behind schedule so that at Neuhardenberg all He 111 tests used only Walter rockets. Von Braun’s 500-kg thrust rockets were not ready until 1938.

Von Braun also worked on the development of rocket boosters, but major difficulties put him behind schedule so that at Neuhardenberg all He 111 tests used only Walter rockets. Von Braun’s 500-kg thrust rockets were not ready until 1938.After conclusion of the He 112 tests using both rocket motors, and the He 111 rocket booster trials, the marquees were dismantled. At the end of 1937, a few days before Christmas, the last workshop caravan pulled out of Neuhardenberg. This coincided with the construction of Peenemünde.

HEINKEL HE 176

___________________________

During the development programme of the He 112, the term "interceptor" had been coined, and the He 176 was seen as the research machine for the project. The RLM was therefore proposing to have designed for the Luftwaffe a new type of aircraft. By virtue of its enormous rate of climb it would take off almost vertically when an enemy bomber formation came into sight at 6000 to 7000 meters, head for it at full speed, make a banking attack from below at high speed while firing from its machine-guns or cannons, and once the tanks were dry land again.

Because the He 176 development was classified top secret, Heinkel set up a special department in his Rostock-Marienehe works. A wooden barrack hut was erected first for the initial testing. Only very few employees were allowed access. This "shed" was soon converted into a permanent building. The development then progressed very quickly. Meanwhile work also went ahead to build the He 176 mock-up because time was pressing.

Erich Warsitz: "Once we saw the completed mock-up we were all appalled at how small it was. We must all have been thinking, "This thing will never fly!" The 176 was so tiny that it would easily have fitted into one of the rooms at the staff quarters. It was a completely new kind of aircraft which had naturally been designed in a particular way for maximum subsonic speed, and we now saw a host of difficulties which had to be overcome. Safety was the major worry but new inventions frequently call upon us to reject safety in pursuit of the goal."

In an emergency at lower speeds the cockpit cover could be thrown free by the pilot allowing him to make the normal exit by parachute. As Warsitz would be flying this aircraft for the first time at speeds never previously obtained, baling out in the familiar way would have meant certain death. Because of the poor chance of getting free of it, the whole cockpit had to be made ejectable. The cockpit and bulkhead behind Warsitz were fixed to four locks and were not integral to the fuselage. By pulling a lever the cockpit would be then separeted from the fuselage to fall below. After a fall of about 1000 metres the wind resistance would slow the cockpit. Then, by deploying the braking parachute, the vertical descent of the cockpit would restrain relatively quickly to a final speed of 300 kms/hr. Warsitz would then throw off the plexiglass cover, unbuckle his straps, jump out, fall to 800 to 1000 metres and deploy the personal parachute to reach the ground at a speed of about 4 to 5 metres/sec. This ejector-cockpit was the forerunner of the modern ejector seat, obviously quite different technically, but serving the same purpose.

In an emergency at lower speeds the cockpit cover could be thrown free by the pilot allowing him to make the normal exit by parachute. As Warsitz would be flying this aircraft for the first time at speeds never previously obtained, baling out in the familiar way would have meant certain death. Because of the poor chance of getting free of it, the whole cockpit had to be made ejectable. The cockpit and bulkhead behind Warsitz were fixed to four locks and were not integral to the fuselage. By pulling a lever the cockpit would be then separeted from the fuselage to fall below. After a fall of about 1000 metres the wind resistance would slow the cockpit. Then, by deploying the braking parachute, the vertical descent of the cockpit would restrain relatively quickly to a final speed of 300 kms/hr. Warsitz would then throw off the plexiglass cover, unbuckle his straps, jump out, fall to 800 to 1000 metres and deploy the personal parachute to reach the ground at a speed of about 4 to 5 metres/sec. This ejector-cockpit was the forerunner of the modern ejector seat, obviously quite different technically, but serving the same purpose.Obviously one cannot simply just get into a unique new aircraft and take off. Initially the basic, unknown characteristics on the ground have to be ascertained first. Erich Warsitz gradually extended the rolling tests to the point where he would start from the perimeter of the airfield, giving the machine full gas until it lifted off. This would allow him to do a sort of leap into the air, then he would shut down the gas and land.

Erich Warsitz: "In a conventional aircraft, at the moment when one goes to full power one immediately has the ability to steer, that is to say the rudder at the rear needed to keep the heading for take-off has immediate effect due to the airstream from the propellors. Our great difficulty was that the He 176 had no propellor and thus created no wind for the rudder. The rudder only began to take effect during a ground run when one reached take-off speed, and before this had no effect at all. To correct that, on the take-off strip I had to hold the heading by use of the brakes, left or right. This was a very sensitive and dangerous affair, for if a little too much pressure was applied on one side the aircraft would either enter into a spin or the tail would go up and threaten to somersault the machine. Though it happened a few times, we always got away with it."

Until then Heinkel had intentionally avoided demonstrating the machine to the Luftwaffe generals, but in the end a visit by an RLM party led by Udet, Milch and half the General Staff could no longer be put off.

Until then Heinkel had intentionally avoided demonstrating the machine to the Luftwaffe generals, but in the end a visit by an RLM party led by Udet, Milch and half the General Staff could no longer be put off.Erich Warsitz: "After the landing our car fetched me. We drove to the spot where all the generals and Dr Heinkel were standing. Milch was the first to approach me. He offered his congratulations and for my special achievement appointed me Flugkapitän. Udet and all the other witnesses also congratulated me."

Once Erich Warsitz was convinced that he knew all the peculiarities and wrinkles of the aircraft through the programme of rolling trials and short leaps, one fine summer's evening on the 20th of June 1939, he announced spontaneously his decision to attempt the maiden flight immediately. A strange silence fell over all the engineers and assembly workers: nobody spoke, for all sensed that the decisive moment for the future was at hand.

Erich Warsitz: "I was already familiar with the unique acceleration along the runway. With full tanks I needed a longer run for take-off. I kept the aircraft straight using only gentle touches on the brakes. I kept her on the ground while building up a higher tempo, then pulled back lightly on the stick to make a steep ascent. I noticed - while flying at 750 km/hr - that the machine was shooting skywards at an angle of less than 45° without any loss in speed! In order not to wander too far from the airfield I banked left at once. It was a thrilling feeling to fly almost silently over the northern tip of Usedom island at 800 km/hr. I had no time for aerial maneuver, for my fuel would last only one minute and I had to concentrate on the landing. I lost height, swept over the Peene river and came in at 500 km/hr. Once over the airfield boundary I touched the runway a few times as prescribed and rolled the machine to a stop. The world's first manned rocket flight had succeeded!"

Historical oil painting on canvas painted by artist Hans Liska in 1939 on the orders of Adolf Hitler

After the first flights of the He 176 a call came from Udet’s adjutant Oberst Pendele to inform that with immediate effect all future flights, including short leaps, were forbidden on the orders of the Generaloberst. Next day Warsitz learned from Heinkel that a display had been arranged for the Führer. The big air show for Hitler, the Party high-ups and the Luftwaffe Generals was to be at Rechlin. The display by the He 176 was to be included with the show of the newest types at the Rechlin tests centre, but not at Rechlin itself for security reasons. Roggentin airfield was the chosen location.

On 3 July 1939 the Führer arrived at Rechlin at first light. The Rechlin air display began. As part and parcel of the general demonstration, together with all new aircraft types and innovations including bomb containers, the rocket boosters were demonstrated. Shortly before midday the Führer’s car arrived at Roggentin bearing Hitler, Göring, Milch and Udet. The Führer and his entourage then inspected the He 176 closely.

On 3 July 1939 the Führer arrived at Rechlin at first light. The Rechlin air display began. As part and parcel of the general demonstration, together with all new aircraft types and innovations including bomb containers, the rocket boosters were demonstrated. Shortly before midday the Führer’s car arrived at Roggentin bearing Hitler, Göring, Milch and Udet. The Führer and his entourage then inspected the He 176 closely.Erich Warsitz: "When Udet called my name I moved forward smartly to receive the Führer’s handshake. It was a very firm grip, as was his custom, but he did not speak. Dr Heinkel and Udet gave explanations about the machine before everybody withdrew a few hundred metres. I climbed in and made the usual checks. Once the spectators were ready I received the signal to go. With full tanks and maximum all-up weight I needed 300 kms/hr to get the aircraft off the ground, for the tiny machine a remarkable speed! I banked, flew over the Führer at 200 metres, banked again for the touchdown, cut the fuel and swept in at 400 kms/hr. It was a very short flight, but had been successful and had made an impact."

HEINKEL HE 178

___________________________

After the success of the He 176 rocket aircraft, Heinkel was embittered at not receiving the support he expected and needed, for after the first flights it seemed interest in it had died away. This did not mean everybody in decisive positions at the RLM, but the Second World War was imminent, and other concerns took centre stage. The He 176 had been officially supported and developed with the RLM approval almost from inception, but not the He 178. The 178 design was pushed through without the knowledge of the RLM, and it was this small aircraft which was later to usher in the Jet Age.

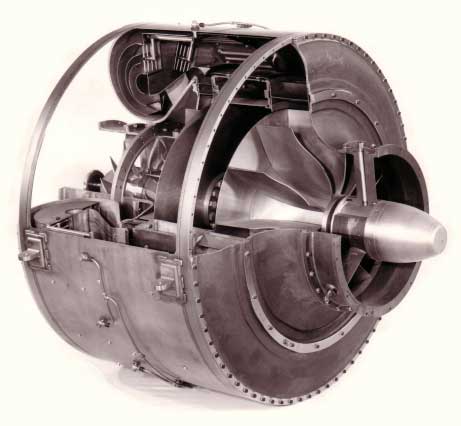

In 1936 Professor Pohl of Göttingen University wrote to Heinkel: “I have here a very capable and innovative man who is working on a jet turbine. We cannot help him any more here because our means are limited. Would you be interested?” Heinkel immediate hired Hans Pabst von Ohain, and assigned him his own laboratory at the Rostock factory and in February 1937 the first turbine ran on the test stand in the ‘special development’ hall with the typical howl known to everybody today. Initially these test runs were never made during working hours but in the evening or at night when only half the labour force would be present, because the engine noise was clearly audible outside the hall. Such was the secrecy.

Erich Warsitz: "It was some considerable time before von Ohain had advanced the He-S3 turbine sufficiently for it to be flight-tested. The turbine would be installed as an auxiliary motor as we had done previously with the von Braun and Walter rockets. We chose the He 118, a heavy two-seater reconnaissance aircraft. It stood well above the ground, and the large undercarriage gave us the necessary clearance to install the turbine below the fuselage. On the third flight the turbine caught fire, however, and although I was able to land straight away, the whole aircraft burned and that put an end to the in-flight testing with that particular engine."

Erich Warsitz: "It was some considerable time before von Ohain had advanced the He-S3 turbine sufficiently for it to be flight-tested. The turbine would be installed as an auxiliary motor as we had done previously with the von Braun and Walter rockets. We chose the He 118, a heavy two-seater reconnaissance aircraft. It stood well above the ground, and the large undercarriage gave us the necessary clearance to install the turbine below the fuselage. On the third flight the turbine caught fire, however, and although I was able to land straight away, the whole aircraft burned and that put an end to the in-flight testing with that particular engine." By the time the second turbine (He-S3A) was finished, Heinkel's team had designed the He 178, in which the engine was installed in early 1939, but the turbine had such poor thrust that no flight could be attempted. The machine was a shoulder-wing airplane of light metal construction, the fuselage of Dural, the high-mounted wooden wings had the characteristic Günter brothers elliptical trailing edge. The jet intake was in the nose, and the plane was fitted with tailwheel undercarriage. The main landing gear was eventually intended to have been made retractable, but remained fixed in its "down" position throughout its flight trials. The He 178 was built with safety in mind, had a wide wheelbase, large brakes and bore no similarities to the He 176.

By the time the second turbine (He-S3A) was finished, Heinkel's team had designed the He 178, in which the engine was installed in early 1939, but the turbine had such poor thrust that no flight could be attempted. The machine was a shoulder-wing airplane of light metal construction, the fuselage of Dural, the high-mounted wooden wings had the characteristic Günter brothers elliptical trailing edge. The jet intake was in the nose, and the plane was fitted with tailwheel undercarriage. The main landing gear was eventually intended to have been made retractable, but remained fixed in its "down" position throughout its flight trials. The He 178 was built with safety in mind, had a wide wheelbase, large brakes and bore no similarities to the He 176.Hans Pabst von Ohain: "Now what was the reason why the turbine was still not as good as we had hoped? We experimented with various combinations to modify the compressor diffuser and turbine nozzle vanes to increase thrust sufficiently to qualify the aircraft for the first flight demonstration. This gave us 450kg thrust, in my opinion 500 kg. We found that a small diffuser behind the engine with a collar and splitter to divert flows functioned better than a high speed flow through the entire tube. The final result of the changes was the He-S3B. Engineer Gundermann worked hard to use the static pressure, limited in the He 178 by the engine frontal area. He hated the adversely long air inlet and jet pipe and argued for a twin-jet version, but nobody wanted to hear this at the time. It would have been too expensive and Heinkel preferred less power and a simple aircraft."

Erich Warsitz: "Not long afterwards von Ohain was ready enough for us to dare flying the 178 with his He-S3B. At the Heinkel works far less attention could now be paid to secrecy. It had become less important, for whereas something could be kept secret in a cellar or some other hideaway, one could hardly do so once the thing was flying. When we flew the He 176 at Peenemünde, the people sunning themselves on the beach at Zinnowitz, 15 kilometres away suddenly heard a tremendous thunder in the sky, and everybody looked. That put an end to the secrecy! Therefore the maiden flight was set intentionally for 0400 because nobody would be at work then and the people of Rostock still safely abed. We knew that they would scramble up – later confirmed – once they heard this aircraft scream past with its unique engine sound, but by then it would be long gone, and they would have seen nothing."

On Sunday, 27 August 1939, only a few days before the outbreak of War, everything was ready. Beautiful weather prevailed, and the Heinkel He 178 was towed to the take-off position. Heinkel himself and his staff looked with some apprehension at the circuit, for meanwhile it had been recognized that the aircraft of the future was not the rocket aircraft but the jet with its longer flight time and greater margin of safety.

On Sunday, 27 August 1939, only a few days before the outbreak of War, everything was ready. Beautiful weather prevailed, and the Heinkel He 178 was towed to the take-off position. Heinkel himself and his staff looked with some apprehension at the circuit, for meanwhile it had been recognized that the aircraft of the future was not the rocket aircraft but the jet with its longer flight time and greater margin of safety. Erich Warsitz: "Like the He 176, the 178 had major differences from a conventional aircraft: the rudder was only effective at higher speeds shortly before take-off so that I would have to use the brakes to keep her straight on the runway. Immediately before the flight I roll-tested the aircraft over a short stretch and noted that the brakes were not only adequate for correcting the heading but superb! The 178 was much larger than the 176, heavier and had at least a 1.3 wheelbase. In the 178 I could sit up correctly: the pilot seat was so located that the intake shaft for the turbine did not obstruct it. Narrow, obviously, but no comparison to the 176 which needed a shoe-horn to fit the pilot in!"

"One last time I checked all the control surfaces for freedom of movement, checked the running turbine at various speeds, checked pump pressures, temperatures and much more besides, then gave the ground-crew the sign to close the canopy. Slowly I applied full-throttle. As the aircraft started moving, I remember feeling a little disappointed at the lack of thrust, because the machine was gathering speed slowly, instead of shooting along like the 176. However, after a ground-run of about three hundred metres it was picking up speed at a very high rate. I found I could hold the machine exactly on course using the brakes, and then the aircraft lifted off. All the control surfaces felt almost completely normal, while the turbine steadily sang its high-pitched song. It was wonderful to be flying; not a trace of wind was blowing, and the sun was just visible, very low on the horizon. I had been told in no uncertain terms that I was to land immediately after a single fairly large circuit, but at that point my enthusiasm overcame me: I accelerated slightly, and thought: oh, just one more circuit, then!”

After the second circuit Warsitz set the aeroplane up for the landing. The turbine responded to the throttle lever very obediently. Just above the ground he corrected the machine’s attitude, pulled off a perfect landing and came to a halt just short of the waters of the Warnow.

The first jet flight in history had succeeded! All the tension evaporated, and everyone was jubilant. The fitters lifted Dr. Heinkel and Erich Warsitz onto their shoulders, and after a short de-briefing in the officers’ mess they headed for the Casino to toast the first triumphant flight pointing the way to the future direction of aviation.

Wernher von Braun and Erich Warsitz in 1959

SECOND WORLD WAR

_____________________________________

When Dr Heinkel revealed his secret achievement to the RLM, he naturally expected an invitation to display his success in decisive quarters. He was soon sobered in his hopes, for with the outbreak of war the following Friday, Berlin had other things on its plate. However, he succeeded a few months later in getting Milch, Udet, Lucht and the entire RLM technical staff to Marienehe to watch an exhibition flight of the He 178. He was certainly counting on the RLM financing him, for the development to date had cost him a pretty pfennig. Subsequently its display Erich Warsitz dedicated himself fully to his work as chief pilot at Peenemünde-West and as an instructor in France.

After the successful flights and experience gained with the purely experimental aircraft He 178 there was nothing left to do but begin planning for a new kind of operational warplane. Heinkel slipped into gear automatically, from the designers and stress analysts to the constructors, and so the He 280 was conceived. The nose wheel was indispensable, for at take-off the machine was then easy to keep on its heading without danger of it straying laterally. With the He 176 and He 178 this could only be cured by braking on the opposite side to the veer and that despite the necessary fine touch, especially with the He 176, it led to countless dangerous ground spins and also to wingtip contact with the ground and resultant wing or tailplane damage.

The He 280 had to be fitted with two He-S8 turbines slung below the wings in order to avoid the intake and exhaust shafts as in the He 178 airframe. The maiden flight of the He 280 was made on 30 March 1941 at Marienehe piloted by Fritz Schäfer. This was the first ever flight by an aircraft powered by two jet turbines.

At the time Messerschmitt was working on the Me 262, which Fritz Wendel test flew for the first time at Leipheim on 18 July 1942. The aircraft had difficulty lifting off because the elevator was ineffective at low speed and the pilot had briefly to touch the brakes to bring the aircraft horizontal for take off. The Me 262 became the world's first operational jet-powered fighter aircraft in World War II.

Erich Warsitz: "I flew the He 280 on several occasions for research purposes. There were vibrations at the tail and the design lacked a pronounced supersonic wing profile. The Me 262, which I also flew, was not yet ideal: it was improved later and, especially when fitted with Jumo 004 turbines, was superior to the He 280 in every respect, although this was not the factor which decided the RLM in favour of the Me 262. In contrast to Heinkel, Willy Messerschmitt was the decisive ideas man and designer to the end. One of his talents was skilfully to railroad major conferences. To get his own way he had no inhibitions about doctoring the figures. Heinkel on the other hand lacked diplomatic skill and would quickly hit the roof under pressure, as I witnessed several times at RLM conferences. This was probably the reason for his oft-cited aversion to the RLM, and of them for him. Therefore some at RLM used the temporary disapproval of Heinkel to swing the decision in favour of Messerschmitt. Though Udet was a close friend of Heinkel, he could not always shelter him. After Udet's suicide on 17 November 1941, it followed that Milch should eventually close the books on the He 280 in March 1943."

In the summer of 1943, RLM invited manufacturers to submit designs for a light jet fighter. Heinkel designed a simple jet monoplane with an He-S 011 turbine mounted on the roof of the fuselage. This was the future He 162 Volksjäger. After RLM had been absorbed into the Armaments Staff, in October 1944 Heinkel received the first orders to build 1000 machines even before the first prototype had flown. It was intended that the He 162 should become the standard single-engine jet fighter of the Luftwaffe, but the chaotic conditions in Germany during the last year of war ensured that only a handful were operational by the close.

In the summer of 1943, RLM invited manufacturers to submit designs for a light jet fighter. Heinkel designed a simple jet monoplane with an He-S 011 turbine mounted on the roof of the fuselage. This was the future He 162 Volksjäger. After RLM had been absorbed into the Armaments Staff, in October 1944 Heinkel received the first orders to build 1000 machines even before the first prototype had flown. It was intended that the He 162 should become the standard single-engine jet fighter of the Luftwaffe, but the chaotic conditions in Germany during the last year of war ensured that only a handful were operational by the close.Erich Warsitz: "Although I was no longer at Heinkel's, in the autumn of 1940 Udet allowed me – certainly because of my experience – to take part in an RLM conference called to discuss the He 280. In this conference, from which industry was excluded, I pointed out amongst other things the difficulties we had experienced after Hitler told me that the 18 months required for the He 178 was too long and the whole project would come too late; I shall never forget the Führer-Directive ordering all developments not ready for mass-production within a year to be suspended with immediate effect. I was to be proved right, some years later. When enemy bombers held the skies over Germany and there was a shortage of fighters, the jet programme received the highest priority, but too late."

Besides the Me 262 and He 162, which had a negligible impact on the course of the war as a result of their late introduction and the consequently small numbers put in operational service, another aircraft deserves to be mentioned: The Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet, which was developed and tested independently of the He 176, became the first and only operational rocket-powered interceptor, although ineffective in its dedicated role. But on October 2, 1941 the Me 163A was the first aircraft of any type to break the magic mark of 1.000 km/h with test pilot Heini Dittmar at the command. This record-breaking flight was unofficial but unmatched by turbojet-powered aircraft for almost a decade.

Besides the Me 262 and He 162, which had a negligible impact on the course of the war as a result of their late introduction and the consequently small numbers put in operational service, another aircraft deserves to be mentioned: The Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet, which was developed and tested independently of the He 176, became the first and only operational rocket-powered interceptor, although ineffective in its dedicated role. But on October 2, 1941 the Me 163A was the first aircraft of any type to break the magic mark of 1.000 km/h with test pilot Heini Dittmar at the command. This record-breaking flight was unofficial but unmatched by turbojet-powered aircraft for almost a decade.In 1942 during a test flight with an Me 109 Erich Warsitz had an accident – caused by a faulty fuel lead – which put him out of flying for a year. While he was a test pilot his considerable earnings were credited into his bank account. Thus he took over the management of his father’s business and the money left over he invested into the ‘Warsitz Werke’ in Amsterdam making various high-precision materials. On the basis of his experience in the sphere of rocketry, his technical interest and his earlier work with Wernher von Braun, he was involved there in the manufacture of some parts of the A-4 rocket.

POST WAR

________________

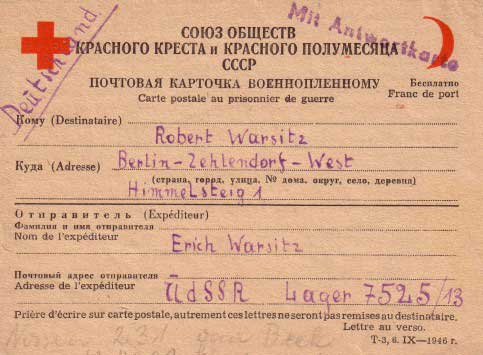

On the night of 5 December 1945 Erich Warsitz was kidnapped from his flat in the American sector of Berlin by four Soviet officers and taken to Berlin-Teltow prison at the barrel of a machine-gun. Thus he vanished, and nobody knew where, including the Americans. From that day on his life was a misery. For weeks on end he endured interrogations every night and was shuttled four times between jails until he finished up in the camp at Hohenschönhausen and a few months later at Sachsenhausen. The innumerable interrogations focused on his Party membership and industrial activities, but the main point of interest was his work on rocket and jet aircraft at OKH and RLM, at Peenemünde and the Heinkel Works. The East, Peenemünde and Rostock being in Russian hands, his former activities were no longer a secret.

Erich Warsitz: "At first I was persona grata in the jails until I refused to sign a contract which would have obliged me to cooperate for five years on the Russian development in rockets and jets – with an alleged flat in Moscow, 6.500 roubles monthly upkeep, etc. etc. It was obvious to me that having witnessed all the things they were up to I would never see my home again. For my refusal I was declared persona non grata and given a medieval third degree in water baths and steam bunkers. At the end of 1946 when I declined the final ultimatum to sign the work contract within three days I was given 25 years’ forced labour and shipped out to the notorious punishment camp 7525/13 in Siberia. We travelled in virtually open rail waggons in temperatures of minus 40°C. Every day there were deaths in the waggons. The bodies were thrown into the snow. After a 35-day long journey with little to eat we arrived in a weakened state in Siberia. There I was put to work in two Soviet armaments factories working initially an 18-hour day. When each night we prisoners returned exhausted and hungry to the camp, shadowed by wolves, there was not infrequently a fight to the death over a slice of bread. Although the Russians themselves had little to eat, their people in Siberia would often roll a few potatoes or an onion to us under the fence. We were all hoping for the next war as our only hope of freedom."

Erich Warsitz: "At first I was persona grata in the jails until I refused to sign a contract which would have obliged me to cooperate for five years on the Russian development in rockets and jets – with an alleged flat in Moscow, 6.500 roubles monthly upkeep, etc. etc. It was obvious to me that having witnessed all the things they were up to I would never see my home again. For my refusal I was declared persona non grata and given a medieval third degree in water baths and steam bunkers. At the end of 1946 when I declined the final ultimatum to sign the work contract within three days I was given 25 years’ forced labour and shipped out to the notorious punishment camp 7525/13 in Siberia. We travelled in virtually open rail waggons in temperatures of minus 40°C. Every day there were deaths in the waggons. The bodies were thrown into the snow. After a 35-day long journey with little to eat we arrived in a weakened state in Siberia. There I was put to work in two Soviet armaments factories working initially an 18-hour day. When each night we prisoners returned exhausted and hungry to the camp, shadowed by wolves, there was not infrequently a fight to the death over a slice of bread. Although the Russians themselves had little to eat, their people in Siberia would often roll a few potatoes or an onion to us under the fence. We were all hoping for the next war as our only hope of freedom."After his return in 1950, thanks to Chancellor of West Germany Konrad Adenauer, he founded his precision mechanical firm “Maschinenfabrik Hilden”, until, in 1965, he retired. In April 1983, Erich Warsitz suffered a stroke and as a result died at the age of 76 on 12 July 1983 at Lugano in Switzerland.

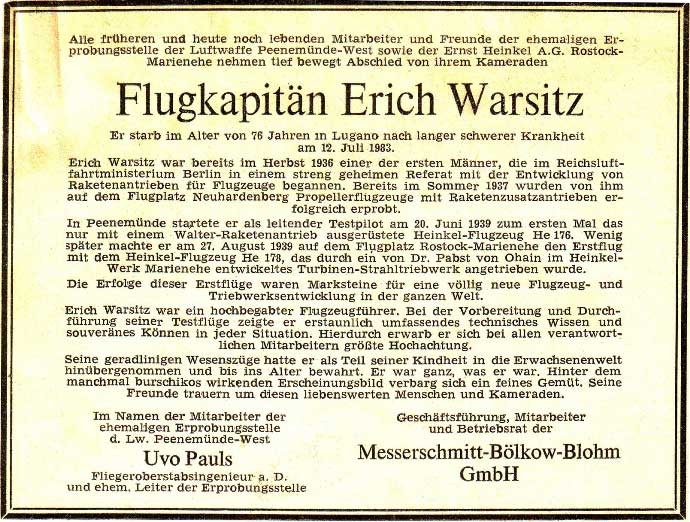

Death Notice by Messerschmitt-Bölkow-Blohm GmbH (today EADS)

Hans Pabst von Ohain - April 14, 1988: "This was the first flight in history by a jet propelled aircraft. Once again, enormously capable as an aviator and courageous, Erich Warsitz flew a new concept. In later years I have often reflected on him. I admire him still and am firmly convinced that his brave preparedness to sacrifice himself, tied to his technical and aeronautical skill, contributed significantly to the rapid development of the jet turbine and rockets for manned flight. His image in the National Air and Space Museum at Washington DC flying the first He 178 will for ever bear witness to that." (see IMAGE >>)

Wernher von Braun - Swiss Museum of Transport - August 30, 1971: "In conclusion I should like to mention another friend who contributed to space travel: Erich Warsitz. In 1939 Erich flew a rocket-propelled aircraft for the first time in history, the Heinkel He 176. Thus it was here that the era of space travel actually began, for these initial rocket flights played an important role in the planning, technology and also the aeronautical aspects of manned space flight."

German aviation pioneers meet at Baden-Baden in 1964

From the left: Dr Ing. Wurster (Messerschmitt), Ernst Seibert (Junkers), Heinz Kindermann (Junkers),

Fritz Wendel (Messerschmitt), Gerhard Nitschke (Heinkel) and Erich Warsitz.

Erich Warsitz in 1982: "At the time of writing with my son Lutz, forty-three years have elapsed since the world's first jet flight, and in the intervening years I have often been asked if I realized at that time that the German rocket and jet test programme would be the decisive step forward. We knew – from our technical espionage service – that the British and Americans had such a project but were not so far advanced as we were. I knew there was nothing similar anywhere in the world, but I was not imagining myself wearing the laurel wreath! All the same I was aware what great advances flights with the He 176 and He 178 would signify, and I was also convinced that within a few years few military and civilian commercial aircraft would still be flying with a piston-engine and propellors. At that time I was called an incurable optimist, but we were correct in thinking then that we had successfully ushered in a new epoch."

First English Jet

Gloster E.28/39

15 May 1941

First American Jet

Bell P-59 Airacomet

1 October 1942

"My wish to experience something revolutionary and sensational came to fruition with the successful moon landing, in which Wernher von Braun played such a decisive role. I often think how the modern Space-Shuttle resembles the minute He 176, also fired into the air by a rocket, and also glided back down to earth – and wonder what more the future in space holds beyond our present imagination! When I reflect on my life today, I have to say that the period of the Thirties was the finest and most exciting time of my life. A great dream was realized, flying became my everything, and what I achieved far exceeded what I had thought for myself at the outset. Looking back I am very proud of that and thank my Creator that I am still around to relate a story which is perhaps still of interest. I wish all aviators a safe landing."

"My wish to experience something revolutionary and sensational came to fruition with the successful moon landing, in which Wernher von Braun played such a decisive role. I often think how the modern Space-Shuttle resembles the minute He 176, also fired into the air by a rocket, and also glided back down to earth – and wonder what more the future in space holds beyond our present imagination! When I reflect on my life today, I have to say that the period of the Thirties was the finest and most exciting time of my life. A great dream was realized, flying became my everything, and what I achieved far exceeded what I had thought for myself at the outset. Looking back I am very proud of that and thank my Creator that I am still around to relate a story which is perhaps still of interest. I wish all aviators a safe landing."

Go back to >>

.

.